Lexington is testing an innovative planting method called a pocket forest. It is a small, dense grove of native trees and shrubs planted close together in prepared soil. The goal is to jump-start a healthy mini-ecosystem that grows quickly and becomes self-sustaining, creating a little biodiversity hotspot right here in town.

Forests are one of our best climate-stabilizing tools, better than individual trees and a key counterpoint to the valuable work of emissions reduction. Forests pull carbon from the air and store it in wood and soil, cool hot places, hold water after storms They also feed and shelter wildlife, helping to preserve biodiversity, vital for all life here on Earth. A pocket forest is a small, working piece of that system. Because the method is simple and low cost, these patches can spread across town to start stitching nature back together and quickly repair degraded land.

This pilot is led by LexCAN board member Rachel Summers through her work on the Town’s Tree Committee in partnership with the town via DPW director, David Pinsonneault. Over the past year, Rachel pre-piloted several small test plots on residential properties sort out the process and to see how simple, DIY-friendly methods could help Lexington expand tree canopy, improve soil, and restore habitat at a lower cost than traditional approaches. The idea is not only to plant one site, but to learn what works and make it easy for residents to try similar projects at home.

As explained on the project web page, “This pilot project captures stormwater, carbon, and pollution, while creating shade, cooling, and providing habitats for birds, bees, and butterflies. The idea is simple but powerful: maximum ecological function per square foot, using low-tech, low-cost methods.”

More info about the project history / local press from The Lexington Times / Jane Whitehead.

You can learn more in this short slide presentation:

Why this can scale

Pocket forests are low tech and accessible, and can even grow without supplemental watering – using wood chip mulch for passive rainwater capture, opening up many other viable sites. They fit into small spaces yet can filter water, cool the ground, and support a surprising amount of life. Work days double as hands-on education and community building, and the same method adapts easily to backyards, school edges, and other public nooks.

What it costs

Pricing will depend on a few factors, such as whether labor is paid or volunteer / diy, and how – and when – trees are sourced. If a municipal or contractor crew handles prep and planting with roughly $20 saplings, a 300-tree pocket forest on about 1,300 square feet comes in near $7,000 all-in. If volunteers handle the labor for a spring planting taking advantage of state forestry $2 sapling sales, the same planting lands near $600. Either way, you get hundreds of native stems establishing together, which means faster shade, habitat, and soil building for the area by Lincoln Fields where spectators will welcome cooler ground and cover.

For comparison, a single 3-inch caliper street tree often runs around $1,000 when you include planting and early maintenance, and survival is still not guaranteed. Larger nursery stock also carries a higher transport and nursery footprint than small saplings. By contrast, pocket forest trees are 1–3-year-old starts, often locally grown or shipped in compact bundles, which keeps costs and embodied impacts low while allowing many more trees to be planted for the same budget.

First Volunteer Event: Site Prep

On September 20 we combined LexCAN’s Sun Day celebration with a soil-prep work party at Lincoln Fields. About 40 neighbors showed up. Using only hand tools, we laid clean cardboard to smother the tired turf and spread several inches of arborist wood chips on top. Both inputs are waste materials that can be repurposed to rebuild soil structure and retain moisture. With this many helpers, we were done in an hour!

Up Next: Tree Planting

On November 1 – after a short settling period but before the winter freeze – we will plant a diverse mix of native trees and shrubs at tight 2′ spacing. The trees are coming from a 50/50 combination of local grower, 1 Acre of Trees, and residents’ yards. Over the next few years we expect a small, shady grove that supports pollinators and birds, soaks up stormwater, and offers a living example residents can adapt at home. We don’t expect 100% survival, but we do expect somewhere between 60 and 80% to make it through the first season, after which they should begin shooting up quickly.

Our method and the growing movement

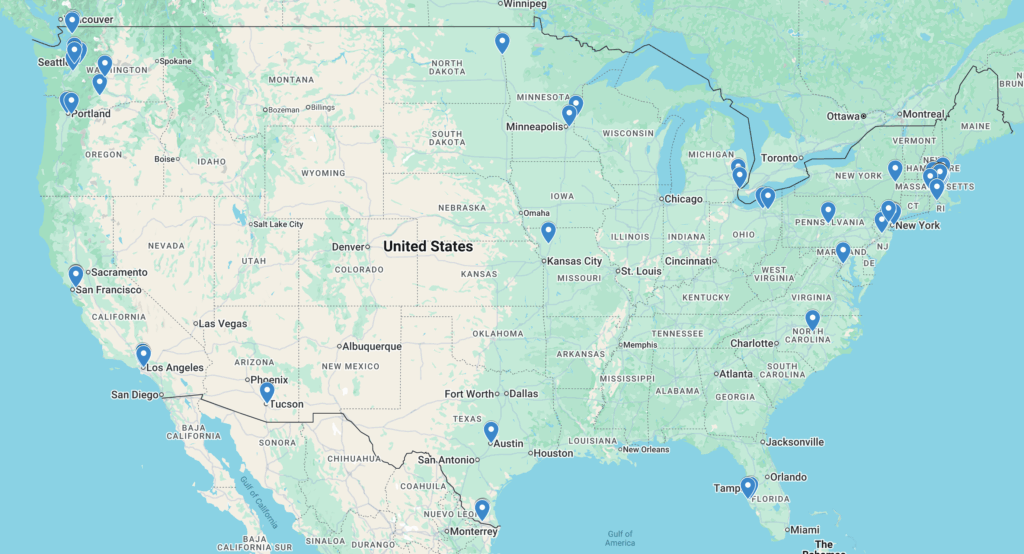

We are following Basil Camu’s pocket forest approach, a cost- and operations-optimized take on Miyawaki-style mini forests that emphasizes practical steps, small stock, and repeatable community workflows. We are also at the front end of a national mini-forest wave, with the Boston area emerging as a US epicenter thanks to many local pilots and strong community interest. If you are curious about where projects are popping up, explore this community map of known US sites. (Map compiled by Rachel Summers. Community contributions welcome.)

How to get involved

- Volunteer at the planting day, or check back for additional volunteer work events at Lincoln Park.

- Learn the method and try a mini version in your yard or with a class or club.

- Share the slides and Miyawaki overview with a neighbor, class, or club.

- Tell us what you notice as the site changes through the seasons.

There is plenty to worry about in climate news, but planting together is a simple, hopeful act that builds skill and community. One small forest at a time, we can make Lexington cooler, greener, and more alive.